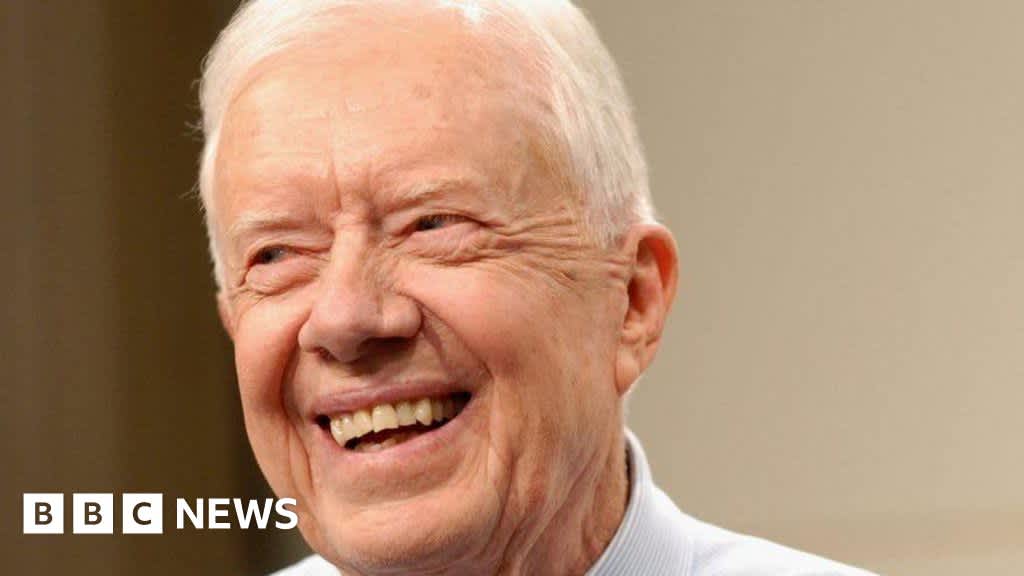

Jimmy Carter, who has died at the age of 100, swept to power promising never to lie to the American people.

In the turbulent aftermath of Watergate, the former peanut farmer from Georgia pardoned Vietnam draft evaders and became the first US leader to take climate change seriously.

On the international stage, he helped to broker an historic peace agreement between Egypt and Israel, but he struggled to deal with the Iran hostage crisis and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

After a single term in office, he was swept aside by Ronald Reagan when he won just six states in the 1980 election.

Having left the White House, Carter did much to restore his reputation: becoming a tireless worker for peace, the environment and human rights, for which he was recognised with a Nobel Peace prize.

The longest-lived president in US history, he celebrated his 100th birthday in October 2024. He had been treated for cancer and had spent the last 19 months in hospice care.

James Earl Carter Jr was born on 1 October 1924 in the small town of Plains, Georgia, the eldest of four children.

His segregationist father had started the family peanut business, and his mother, Lillian, was a registered nurse.

Carter’s experience of the Great Depression and staunch Baptist faith underpinned his political philosophy.

A star basketball player in high school, he went on to spend seven years in the US Navy – during which time he married Rosalynn, a friend of his sister’s – and became a submarine officer. But on the death of his father in 1953, he returned to run the ailing family farm.

The first year’s crop failed through drought, but Carter turned the business around and made himself wealthy in the process.

He entered politics on the ground floor, elected to a series of local school and library boards, before running for the Georgia Senate.

American politics was ablaze following the Supreme Court’s decision to desegregate schools.

With his background as a farmer from a southern state, Carter might have been expected to oppose reform – but he had different views to his father.

While serving two terms in the state Senate, he avoided clashes with segregationists – including many in the Democratic party.

But on becoming Georgia governor in 1970, he became more overt in his support of civil rights.

“I say to you quite frankly,” he declared in his inaugural speech, “that the time for racial discrimination is over.”

He placed pictures of Martin Luther King on the walls of the capitol building, as the Ku Klux Klan demonstrated outside.

He made sure that African Americans were appointed to public offices.

However, he found it difficult balancing his strong Christian faith with his liberal instincts when it came to abortion law.

Although he supported the rights of women to terminate pregnancy, he refused to increase funding to make this possible.

As Carter launched his campaign for the presidency in 1974, the nation was still reeling from the Watergate scandal.

He put himself forward as a simple peanut farmer, untainted by the questionable ethics of professional politicians on Capitol Hill.

His timing was excellent. Americans wanted an outsider and Carter fitted the bill.

There was surprise when he admitted (in an interview with Playboy magazine) that he had “committed adultery in my heart many times”. But there proved to be no skeletons in his closet.

Yet, just nine months later, he toppled the incumbent president Gerald Ford, a Republican.

On his first full day in office, he pardoned hundreds of thousands of men who had evaded service in Vietnam – either by fleeing abroad or failing to register with their local draft board.

One Republican critic, Senator Barry Goldwater, described the decision as “the most disgraceful thing that a president has ever done”.

Carter confessed that it was the hardest decision he had made in office.

He appointed women to key positions in his administration and encouraged Rosalynn to maintain a national profile as First Lady.

He championed (unsuccessfully) an Equal Rights Amendment to the US Constitution which would have promised legal protection against discrimination on the grounds of sex.

One of the first international leaders to take climate change seriously, Carter wore jeans and sweaters in the White House, and turned down the heating to conserve energy.

He installed solar panels on the roof – which were later taken down by President Ronald Reagan – and passed laws to protect millions of acres of unspoiled land in Alaska from development.

His televised “fireside chats’” were consciously relaxed, but this approach seemed too informal as problems mounted.

As the American economy slipped into recession, Carter’s popularity began to fall.

He tried to persuade the country to accept stringent measures to deal with the energy crisis – including gasoline rationing – but faced bitter opposition in Congress.

Plans to introduce a universal healthcare system also foundered in the legislature, while unemployment and interest rates both soared.

His Middle East policy began in triumph, with President Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Begin of Israel signing the Camp David accords in 1978.

But success abroad was short-lived.

The revolution in Iran, which led to the taking of American hostages, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan were severe tests.

Carter broke off diplomatic relations with Tehran and implemented trade sanctions in a desperate effort to free the Americans.

An attempt to rescue them by force was a disaster, leaving eight American servicemen dead.

The incident almost certainly put an end to any hope of re-election.

Carter fought off a serious challenge from Senator Edward Kennedy for the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination, and achieved 41% of the popular vote in the subsequent election.

But it was not nearly enough to see off his Republican opponent, Ronald Reagan.

The former actor swept into the White House with an electoral college landslide.

On the last day of his presidency, Carter announced the successful completion of the negotiations for the release of the hostages.

Iran had delayed the time of their departure until after President Reagan was sworn in.

On leaving office, Carter had one of the lowest approval ratings of any US president. But in subsequent years, he did much to restore his reputation.

On behalf of the US government, he undertook a peace mission to North Korea which ultimately resulted in the Agreed Framework, an early effort to reach an accord on dismantling its nuclear arsenal.

His library, the Carter Presidential Center, became an influential clearing house of ideas and programmes intended to solve international problems and crises.

In 2002, Carter became the third US president, after Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, to win the Nobel Peace Prize – and the only one to earn it for his post-presidency work.

“The most serious and universal problem,” he said in his Nobel lecture, “is the growing chasm between the richest and the poorest people on earth.”

With Nelson Mandela, he founded The Elders, a group of global leaders who committed themselves to work on peace and human rights.

In retirement, Carter opted for a modest lifestyle.

He eschewed lucrative speaking appearances and seats on corporate boards for a simple life with Rosalynn in Plains, Georgia, where both were born.

Carter did not want to make money from his time in the Oval Office.

“I don’t see anything wrong with it; I don’t blame other people for doing it,” he told the Washington Post. “It just never had been my ambition to be rich.”

He was the only modern president to return full-time to the house he had lived in before he entered politics, a single-floor, two-bedroom home.

According to the Post, the Carters’ home was valued at $167,000 – less than the Secret Service vehicles parked outside to protect them.

In 2015, he announced that he was being treated for cancer, the disease that killed both his parents and three sisters.

Just a few months after surgery for a broken hip, he was back to work as a volunteer builder with Habitat for Humanity.

The former president and his wife began work with the charity in 1984, and helped to repair more than 4,000 homes in the years since.

He continued to teach at a Sunday school at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, sometimes welcoming Democratic presidential hopefuls to his class.

In November 2023, Rosalynn Carter died. In tribute, the former president said that his wife of 77 years was “my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished”.

Celebrating his centenary a year later, Carter proved that he still had political antennae.

“I’m only trying to make it to vote for Kamala Harris” in November’s election, he said.

He did manage to cast a ballot for her, although his home state of Georgia ultimately voted for Donald Trump.

Carter’s political philosophy contained the sometimes conflicting elements of a conservative small-town upbringing, and his natural liberal instincts.

But what really drove his lifetime of public service were his deeply held religious beliefs.

“You cannot divorce religious belief and public service,” he said.

“I’ve never detected any conflict between God’s will and my political duty. If you violate one, you violate the other.”

Source: www.bbc.com