Wikipedia Searches Reveal Differing Styles of Curiosity

Mapping explorers of Wikipedia rabbit holes revealed three different styles of human inquisitiveness: the “busybody,” the “hunter” and the “dancer.”

Join Our Community of Science Lovers!

The website Wikipedia describes curiosity as a “quality related to inquisitive thinking, such as exploration, investigation, and learning, evident in humans and other animals.” But there is a lot more to this prime motivator for so much of human behavior—and Wikipedia, as the world’s largest encyclopedia, is now helping social scientists deepen the definition of curiosity.

Tracing how Wikipedia searchers flit among topics and lose themselves in Wiki rabbit holes revealed three different styles of human inquisitiveness: the “busybody,” the “hunter” and the “dancer.”

“Curiosity actually works by connecting pieces of information, not just acquiring them.” —Dani Bassett, University of Pennsylvania

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In this lexicon, a busybody traces a zigzagging route through many often distantly related topics. A hunter, in contrast, searches with sustained focus, moving among a relatively small number of closely related articles. A dancer links together highly disparate topics to try to synthesize new ideas. “Curiosity actually works by connecting pieces of information, not just acquiring them,” says University of Pennsylvania network scientist Dani Bassett, cosenior author on a recent study of these curiosity types in Science Advances. “It’s not as if we go through the world and pick up a piece of information and put it in our pockets like a stone. Instead we gather information and connect it to stuff that we already know.”

The team tracked more than 482,000 people using Wikipedia’s mobile app in 50 countries or territories and 14 languages. The researchers charted these users’ paths using “knowledge networks” of connected information, which depict how closely one search topic (a node in the network) is related to another. Beyond just mapping the connections, they linked curiosity styles to location-based indicators of well-being, inequality, and other measures.

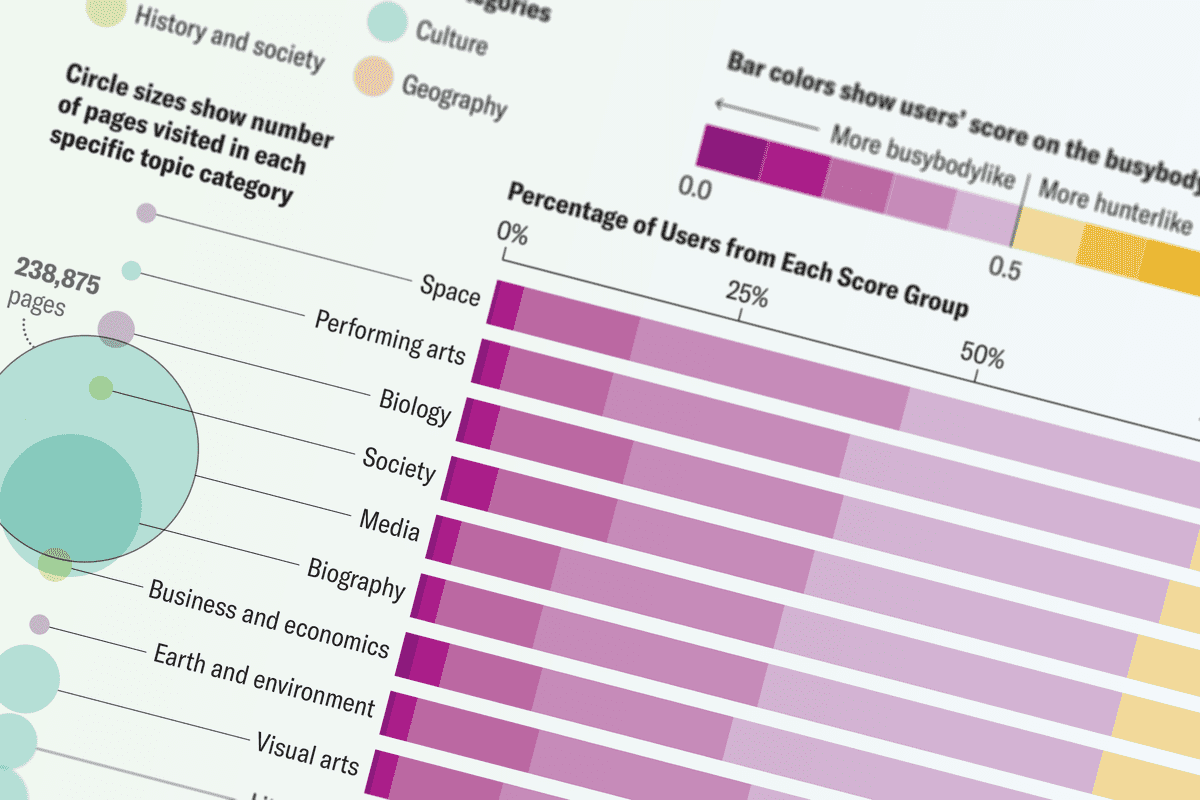

In countries with higher education levels and greater gender equality, people browsed more like busybodies. In countries with lower scores on these variables, people browsed like hunters. Bassett hypothesizes that “in countries that have more structures of oppression or patriarchal forces, there may be a constraining of knowledge production that pushes people more toward this hyperfocus.” The researchers also analyzed topics of interest, ranging from physics to visual arts, for busybodies compared with hunters (graphic). Dancer patterns, more recently confirmed, were excluded.

Gary Stix, senior editor of mind and brain topics at Scientific American, edits and reports on emerging advances that have propelled brain science to the forefront of the biological sciences. Stix has edited or written cover stories, feature articles and news on diverse topics, ranging from what happens in the brain when a person is immersed in thought to the impact of brain implant technology that alleviates mood disorders such as depression. Before taking over the neuroscience beat, Stix, as Scientific American‘s special projects editor, was responsible for the magazine’s annual single-topic special issues, conceiving of and producing issues on Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin, climate change and nanotechnology. One special issue he oversaw on the topic of time in all of its manifestations won a National Magazine Award. With his wife Miriam Lacob, Stix is co-author of a technology primer called .

Source: www.scientificamerican.com