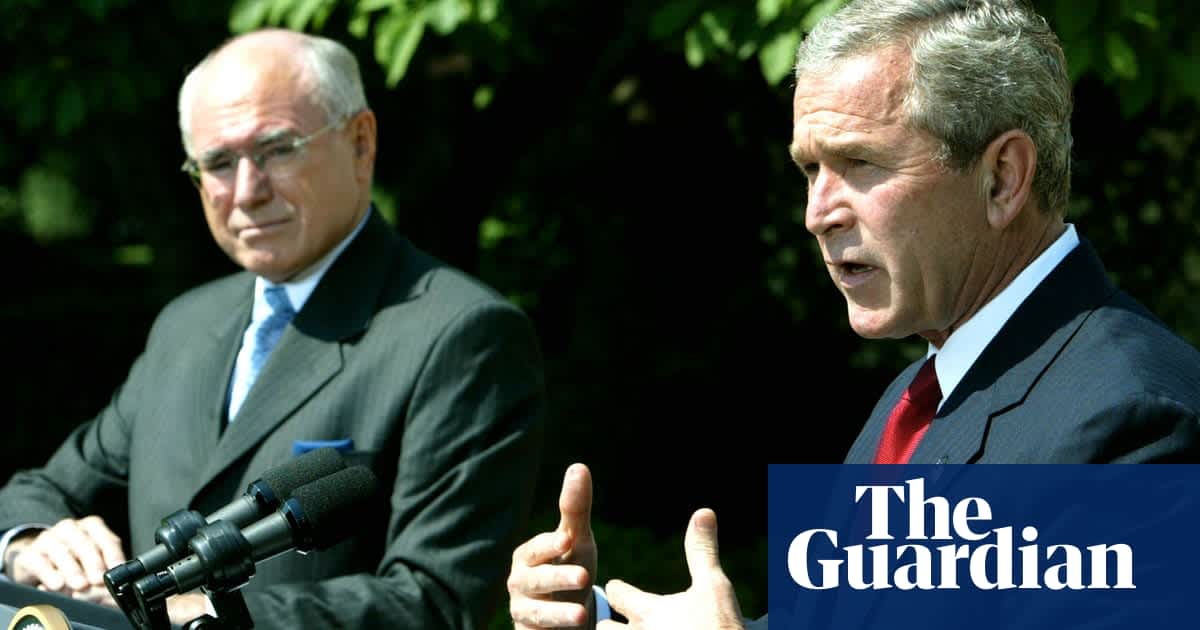

The Howard government sent military personnel to the Middle East well before officially authorising Australia’s involvement

The Howard government avoided disclosing that it had sent military forces to the Middle East months before authorising Australia’s official involvement in the Iraq war in 2003, cabinet records show.

Cabinet documents from 2003 and 2004 released by the National Archives contain the first confirmation of what has been widely discussed in the decades since: the government deployed forces well before officially authorising Australia’s involvement in the war on 18 March 2003.

Public as of 1 January under the law that lifts the seal on all but the most sensitive cabinet records after 20 years, the 2004 documents show how determined the government was to keep the matter secret.

Records from the year before, made public belatedly in March this year after they went missing and were omitted from last year’s 1 January release, confirmed that forces were sent three months earlier than the government would publicly admit.

Sign up for Guardian Australia’s breaking news email

The national security committee (NSC) met on 10 February 2004 ahead of the government releasing a public version of Defence’s review of the Iraq operations. It was concerned to ensure the advance deployment was not disclosed.

The records show the NSC authorised the forward deployment of forces to the Middle East on 10 January 2003 and had been planning for it as early as August 2002.

Records show the NSC agreed to “give collective authority to approve specific forward deployments of ADF elements” from a list which had been approved in meetings on 26 August and 4 December 2002.

On 10 January 2003 the foreign minister, Alexander Downer, gave an oral briefing on the UN-led search for weapons of mass destruction which included the admission that “there was no confidence that the inspection process would uncover clear evidence of continuing Iraqi weapons of mass destruction programmes”.

But the government and its allies remained convinced.

“There was no question of us altering our policy,” Howard told Guardian Australia in December, in relation to realising the weapons were not there. “We just had to hope that as time went by, we would discover the stockpiles. And we weren’t just dependent on this one single announcement from the Americans.”

The absence of weapons was not confirmed publicly until 2004, when the US Senate and then the CIA published reports finding no evidence. Speaking last month, Howard said he was “disappointed” but not surprised.

“That was a blow,” Howard said. “… I still tenaciously maintain, the decision [to deploy] was taken in good faith.

“We never thought for a moment Australia would pull out of the reconstruction. Definitely not.”

The 10 February 2004 record reveals the government resolved to emphasise concern about weapons in its public messaging.

“The committee also noted the importance of highlighting in the government’s public remarks that Iraq had failed to account for significant quantities of weapons of mass destruction that had been documented by the previous UN inspection process,” the NSC minute said.

Sign up to Breaking News Australia

Get the most important news as it breaks

Although Howard cited the presence and potential of weapons as a key justification for joining the war in his 18 March 2003 announcement, the archives’ cabinet historian, UNSW associate professor David Lee, said it was never the main reason.

“The balance of evidence we’ve seen from the cabinet records from 2003 and 2004 indicate that weapons of mass destruction is not the casus belli – the cause of war – for Australia, but rather Australia’s desire to strengthen the US alliance,” Lee said. He said Howard had been determined to do more to boost the alliance than his predecessors Paul Keating and Bob Hawke had done.

Last year, 82 records were found to be missing, including what turned out to be 14 documents on the Iraq conflict, 13 of those from the NSC.

The missing files were located and a review by former defence department secretary Dennis Richardson found the omission was not deliberate. The archives released the missing Iraq-related records on 14 March.

The Iraq deployment comprised three operations – Bastille, covering pre-deployment and training which transitioned to Falconer, covering combat operations until Saddam Hussein’s government was disarmed, and then Catalyst, through Iraq’s anticipated stabilisation and recovery.

Operation Catalyst began on 16 July, a 12-month commitment of up to 999 Australian personnel. The then defence minister, Robert Hill, went back to cabinet on 29 July seeking more money, explaining the cost of all operations had been underestimated by $637.9m.

The documents show there was growing unease about the cost. In its comments on the July submission, the finance department pushed back on aspects of the request.

It noted that Hill was seeking “retrospective funding approval” for elements of Operation Catalyst. The department said the funding should be approved, then capped.

“Should Defence seek any further expansion or extension of Operation Catalyst, it should absorb the cost,” it said bluntly.

It pointedly noted “rapid acquisition funds” allocated initially were still unspent and that Hill was now seeking to transfer them to current operations. Finance said since the funds were “claimed to be urgently needed before the troops were to deploy to Iraq, where possible any contracts that have not been delivered be cancelled and the saved funds returned to the budget”.

It tallied the cost of all other current operations in Afghanistan, Bougainville and Solomon Islands and the border-protection operation Relex off northern Australia, warning any contemplation of extending the Iraq contribution further should have regard to what had already been spent.

But later that year, cabinet was turning its focus to the commercial opportunities for Australia in a post-Saddam Iraq, especially the lucrative wheat trade, which would become the subject of international controversy by 2005.

Source: www.theguardian.com