Why the Paris Climate Agreement Matters in 5 Graphics

One of President Trump’s first executive orders withdraws the U.S. from the Paris climate agreement. These graphics show why the pact is crucial to curbing the worst effects of global warming

Hours after he was sworn into office, President Donald Trump signed an executive order—among a flurry of such decrees—to once again pull the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement, the international pact aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions to stave off their worst impacts on Earth’s climate.

The move comes just after the planet experienced its first year on record in which the average global temperature exceeded 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above the preindustrial period. Under the landmark 2015 Paris climate accord, countries agreed to try to limit warming to under 1.5 degrees C and “well below” two degrees C (3.6 degrees F).

Trump’s executive order—entitled “Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements”—calls for immediately notifying the United Nations of the U.S.’s withdrawal and states that the pullout is “effective immediately.” Under the agreement, countries cannot fully withdraw until one year after notification. Trump removed the U.S. from the agreement during his first term as well, and that departure took effect in November 2020. Former president Joe Biden brought the U.S. back into the agreement in February 2021.

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Because of the discrepancy in timing in Trump’s order and the terms of the agreement, it remains unclear exactly how the withdrawal will play out. The order also calls for an end to U.S. contributions to international climate finance, however—and it is clear from this directive and other orders issued by Trump that the new administration seeks to undo much of Biden’s work on climate action and to further encourage already soaring levels of U.S. oil and gas production.

Numerous climate scientists and advocates have decried the withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and have warned of the dire consequences of failing to act on the climate crisis. “This short-sighted move shows a disregard for science and the well-being of people around the world, including Americans, who are already losing their homes, livelihoods, and loved ones as a result of climate change,” said Jonathan Foley, executive director of Project Drawdown, a nonprofit organization focused on climate solutions, in a recent news release.

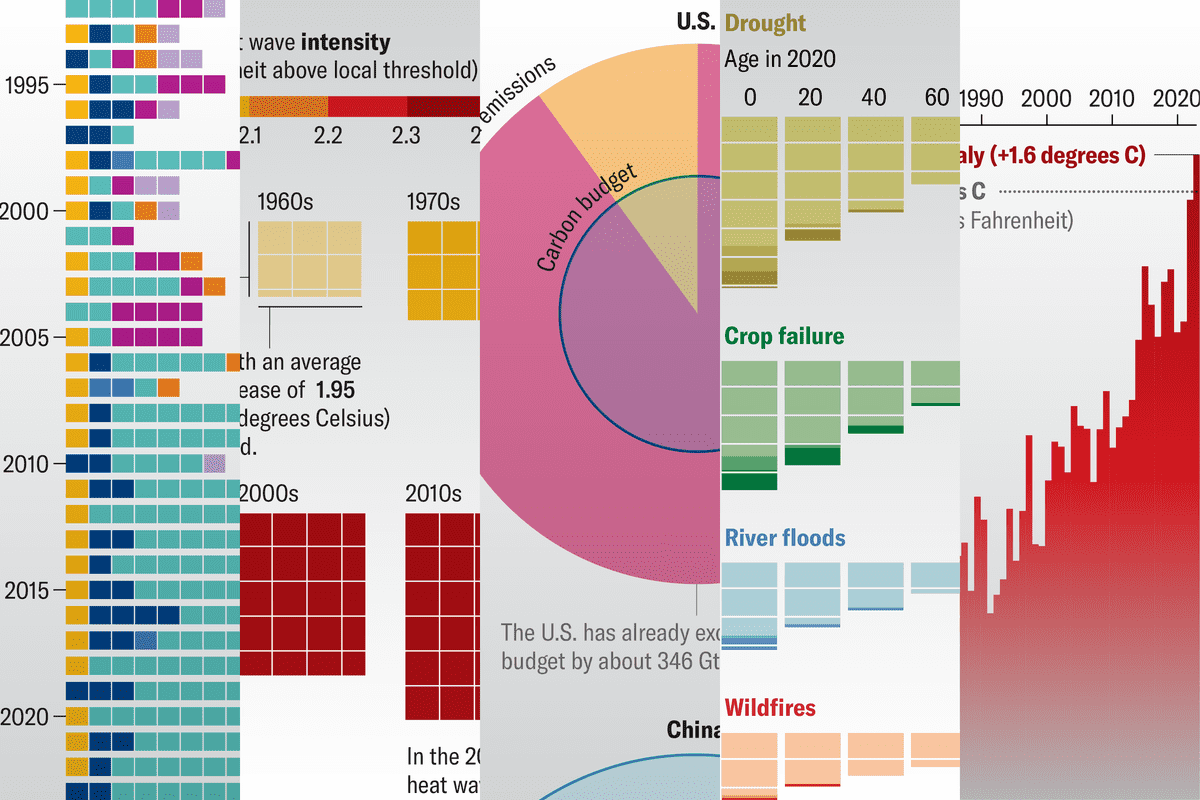

Below are five graphics that show why the Paris Agreement and its goals matter.

The year 2024 was the first on record in which global temperatures registered 1.5 degrees C above the preindustrial period (generally defined as the second half of the 19th century). This marks how much temperatures have risen as humans have continued to burn fossil fuels, sending heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. And it shows how close the world is to breaching the Paris climate accord’s goal. That threshold hasn’t yet been officially surpassed, though, because the agreement considers the average global temperature over many years. So there is still time to limit warming as much as possible if countries and industries can act quickly and ambitiously enough.

We are already feeling the sting of climate change from the heat that has built up in Earth’s atmosphere, and that is most clearly seen in extreme heat events. In the U.S. alone, residents have gone from experiencing two heat waves each summer in the 1960s to more than six today—and those heat waves now average four days instead of three. The heat wave season has also lengthened from 20 days in the 1960s to more than 70 days now.

Extreme heat is the deadliest weather phenomenon in the U.S., and the public health threat will only grow as global temperatures rise. So every additional bit of warming the world can avoid has a tangible effect.

Other disasters—such as hurricanes, floods and wildfires—are also being exacerbated by climate change. In combination with changes in where people live and build infrastructure, the costs of disasters are steadily rising and contributing to an insurance crisis.

When the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration began tracking disaster cost data in the 1980s, a disaster that caused at least $1 billion in damage occurred about every three months in the U.S. Now such a disaster happens about every three weeks. And the dollar values of these events’ costs are almost certainly underestimates—underscoring how political rhetoric often points out the price of transitioning to cleaner energy while overlooking the ballooning costs of not acting.

Those costs, and the pain of the disasters that drive them, will be borne by today’s younger generations—who will experience many more heat waves, droughts, floods, wildfires and other deadly, destructive disasters over their lifetime than their parents or grandparents did. But how much that risk rises very much depends on how much warming societies allow. Meeting the Paris Agreement targets would demonstrably lessen the risks.

U.S. involvement in international climate negotiations—the Paris accord in particular—has long been seen as crucial, both because it pressures other countries to be more ambitious and because the U.S. has “overspent” its portion of the world’s carbon budget. Along with other countries nations that led the Industrial Revolution, the U.S. has gained substantial wealth but it has been responsible for more than its fair share of the amount of carbon that humans can release into the atmosphere and still meet the Paris Agreement goals. It remains to be seen how the U.S.’s exit from the Paris accord will affect the actions and goals of other countries.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor covering the environment, energy and earth sciences. She has been covering these issues for 16 years. Prior to joining Scientific American, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered earth science and the environment. She has moderated panels, including as part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Media Zone, and appeared in radio and television interviews on major networks. She holds a graduate degree in science, health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a B.S. and an M.S. in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology. Follow Thompson on Bluesky @andreatweather.bsky.social

Source: www.scientificamerican.com