4,800-Year-Old Teeth Yield First Human Genome from Ancient Egypt

Forty years after the first effort to extract mummy DNA, researchers have finally generated a full genome sequence from an ancient Egyptian, who lived when the earliest pyramids were built

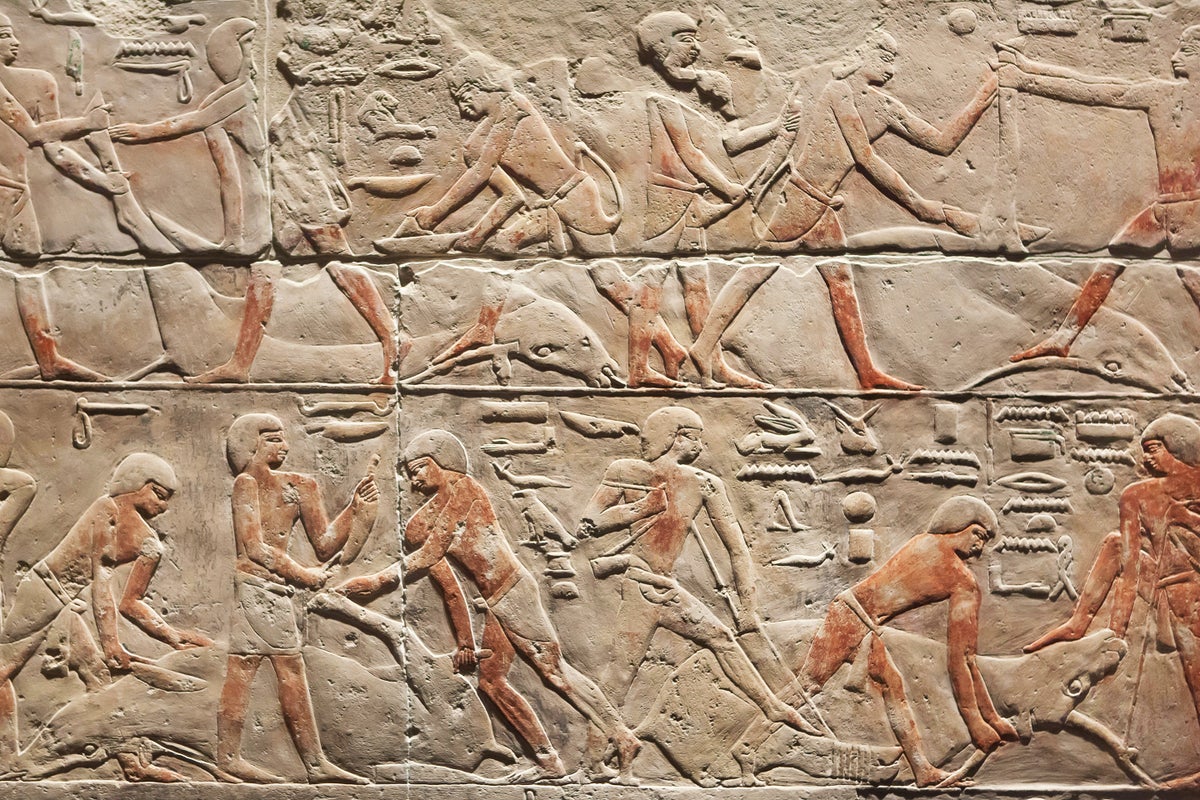

The Ancient Egyptian Old Kingdom (2686–2125 B.C.) produced many lasting artefacts—but little DNA has survived.

Teeth from an elderly man who lived around the time that the earliest pyramids were built have yielded the first full human genome sequence from ancient Egypt.

The remains are 4,800 to 4,500 years old, overlapping with a period in Egyptian history known as the Old Kingdom or the Age of Pyramids. They harbour signs of ancestry similar to that of other ancient North Africans, as well as of people from the Middle East, researchers report today in Nature.

“It’s incredibly exciting and important,” says David Reich, a population geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, who was not involved in the study. “We always hoped we would get our first ancient DNA from mummies.”

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Numerous labs have tried to extract DNA from ancient Egyptian remains. In 1985, evolutionary geneticist Svante Pääbo reported the first ancient DNA sequences from any human: several thousand DNA letters from a 2,400-year-old Egyptian mummy of a child. But Pääbo, who won a Nobel prize in 2022 for other work, later realized that the sequences were contaminated with modern DNA — possibly his own. A 2017 study generated limited genome data from three Egyptian mummies that lived between 3,600 and 2,000 years ago.

The hot North African climate speeds up the breakdown of DNA, and the mummification process might also accelerate it, said Pontus Skoglund, a palaeogeneticist at the Francis Crick Institute in London who co-led the Nature study, at a press briefing. “Mummified individuals are probably not a great way to preserve DNA.”

The ceramic vessel in which the remains of the Nuwayrat individual were discovered.

Skoglund says his expectations were low when his team extracted DNA from several teeth from the Nuwayrat individual. But two samples contained enough authentic ancient DNA to generate a full genome sequence. Y-chromosome sequences indicated that the remains belonged to a male.

The majority of his DNA resembled that of early farmers from the Neolithic period of North Africa around 6,000 years ago. The rest most closely matched people in Mesopotamia, a historical Middle Eastern region that was home to the ancient Sumerian civilization, and was where some of the first writing systems emerged. It’s not clear whether this implies a genetic direct link between members of Mesopotamian cultures and people in ancient Egypt — also hinted at by similarities in some cultural artefacts — or whether the man’s Mesopotamian ancestry arrived through other unsampled populations, the researchers say.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on July 2, 2025.

Ewen Callaway is a senior reporter at Nature.

First published in 1869, Nature is the world’s leading multidisciplinary science journal. Nature publishes the finest peer-reviewed research that drives ground-breaking discovery, and is read by thought-leaders and decision-makers around the world.

Source: www.scientificamerican.com