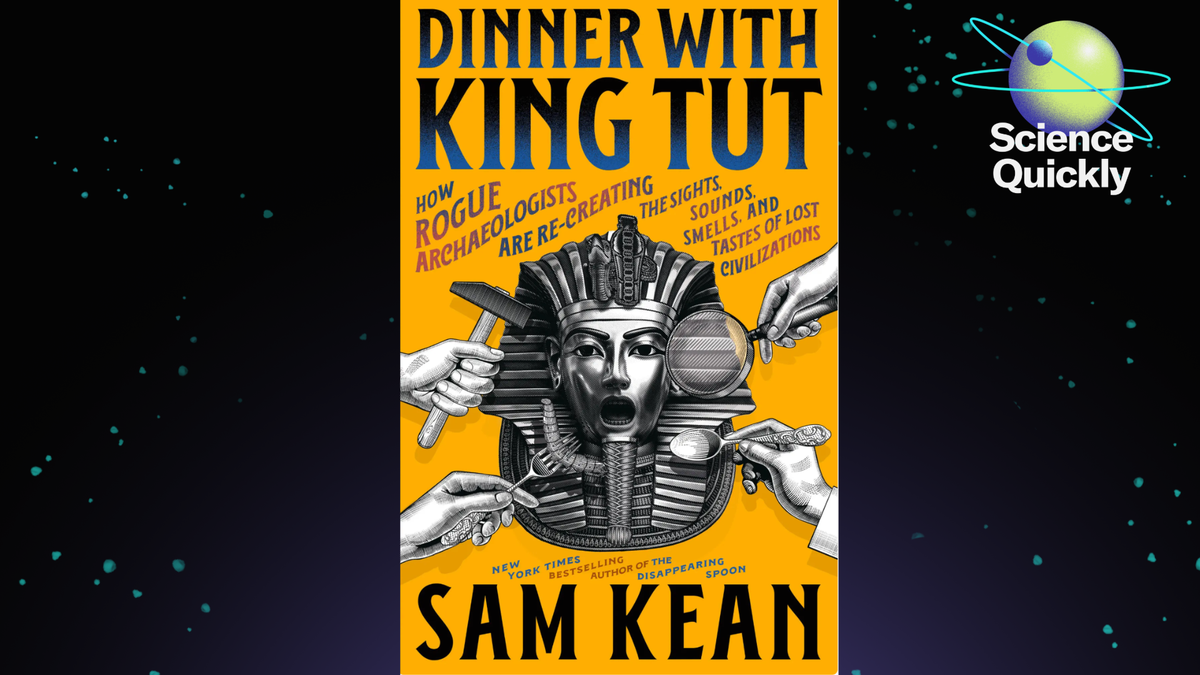

Sam Kean’s New Book Dinner with King Tut Explores the Wild World of Experimental Archaeology

In his new book, Sam Kean reveals how re-creating ancient tools, techniques and traditions can unlock secrets about how our ancestors lived—and what they felt.

Rachel Feltman: For Scientific American’s Science Quickly, I’m Rachel Feltman.

Our guest today is Sam Kean, a science writer who’s written seven books. His latest is called Dinner with King Tut, and it explores the world of experimental archaeology. He’s tried his hand at everything from ancient brain surgery to mummifying a fish, and he’s here to tell us all about it.

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Thanks so much for coming on to chat today.

Sam Kean: Well, thanks for having me.

Kean: Well, for the book I got to attend an authentic Roman banquet [laughs], which was pretty cool. I got to try my hand at ancient surgery and tattooing. There’s a lot of food stuff out there; that’s probably the best entrée for people wanting to get involved, is just try to make some ancient recipes—you know, some heirloom grains, things like that. I made a fish mummy at one point for the book, and that was surprisingly easy to do, so you can mummify a fish or, you know, another small animal, something like that.

So there’s a lot of cool things to do, and it kind of runs the gamut, again, from everyday things like food and tools all the way up to catapults and boats and people—making human mummies, even stuff like that. So there’s really a range of activities.

Feltman: Yeah, well, and I think even some folks who, you know, have maybe come across some of these projects, like people making perfume that smells like a mummy, might be surprised at how hands-on you were able to get in the book. Could you tell us some more about some of the things you were able to experience while you were researching?

Kean: Yeah, so, like, the catapult I got to see was pretty amazing. This guy made a 30-foot tall, medieval—authentic medieval catapult. And we spent a day out—he built this in Utah—we spent a day out there in the mountains, throwing these giant garden stones around at this wall that he had built that was 250 yards away, and it was pretty magical being out there and getting to see this thing fire—being able to fire it myself, actually. So that stands out as something. That, that was probably the most fun thing I did for the book, was [laughs] seeing that giant catapult.

Then there were some things, some days, that were really painful and awful. Like, the, the surgery that I mentioned that I did, it was a, a surgery called a trepanation, so you’re removing a bit of the skull, essentially. And it’s startling to think about, but this is one of the most ancient surgeries …

Feltman: Mm.

You can get a really, really sharp edge on a stone tool, and obsidian even—it’s a type of volcanic rock—you can get a sharper edge on that than even modern surgical-steel scalpels …

Feltman: Wow.

Kean: They form a really, really sharp edge. The problem with stone tools is that they wear down quickly …

Feltman: Right.

Kean: And so after I made the first, initial cut—I was removing a triangular-shaped piece—after I, I made the initial cut, the one leg of the triangle, it went really well for the first cut, but after that the stone tool got worn down, and after that it was just a war of attrition …

Feltman: Mm.

Kean: Of me sort of grinding my way through this skull. I was just sitting there—there were flies biting me; it was hot. I was really upset and getting frustrated. But that was a good learning experience in and of itself, just to show you what something basic like medicine was like back then.

And the emotions eventually became an important part of the process. Learning things like that, you know, you get frustrated, but it really stuck with me, and it made me appreciate just how difficult things were for our ancestors and made me appreciate the fact that they did all this work and we wouldn’t be here if they hadn’t.

Feltman: Yeah, did those hands-on experiences change your perspective of the past in any other ways, beyond just appreciating how difficult things were?

Feltman: Mm.

So by running these experiments you can learn things and you can rule some things out. So I think it’s valuable ’cause it can actively teach us things about the past. And I think by doing certain things, even something basic like making bread or beer or something like that, you start to ask more questions and different questions, and it teaches you aspects of the process that you would not have thought to ask about otherwise.

Feltman: Mm.

Kean: For their conclusion. So it can help you avoid going down wrong paths, and in some cases it can answer questions or evoke questions that we just wouldn’t ask otherwise.

Feltman: Yeah, very cool, and I mean, I’m sure this really runs the gamut, but in your experience who are the people who are creating these experiments? You know, how are they getting interested in these questions?

Then there are amateurs, people who just got obsessed [laughs] with some topic—and amateurs in the best sense of the word, in that they just loved the topic and wanted to learn all they could about it. They’re not getting paid to do it, but they have a deep knowledge of the field, and they just decided to try something new and different. So they are a part of the field as well.

And then another really important aspect is there’s a lot of native and Indigenous communities who have either kept traditions alive or they’re trying to revive traditions that got stamped out by colonialism, missionaries, whatever the case was. And in a lot of cases they’re the ones going to the archaeologists and teaching them how things were based on either things they have kept alive or lore they might know.

So all of those groups are kind of working together, and I think that’s part of the fun of the field, is that you can get insights from a lot of different people in a lot of different places. So it was fun to meet all of ’em.

Feltman: Did any of the experiments you participated in in the book change the way you do things in everyday life? Like, I don’t know, for example, have you picked up some Roman culinary techniques [laughs] or anything of that nature?

Kean: One thing it did do: I sort of view the world itself a little differently in that …

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Kean: Before I would walk down the street where I live in D.C., and there were a lot of trees in this neighborhood, but before to me it was just sort of this green canopy overhead; it was almost like decoration. And now I see it and I, I’m better about telling individual trees apart—you know, “This is this type of tree. This is this type of tree.” And I also look at the trees differently because I can see them as, you know, a resource: the wood that they have—the acorns that they have are a food source. So I look at things like that differently, and—even, like, rocks on the ground, I can look at those and say, “Oh, that’d be a good hammerstone for making tools,” or “That’s a good type of rock to make a tool with.”

So I feel a little more connected in the sense that it’s not just, again, decoration, it’s more, you know, their resources, and I feel like I understand that aspect of nature better because of the experiences I had.

Feltman: And is there anything that you really wanted to try that you, you weren’t able to?

Kean: I did get to do, in Micronesia, a little bit with navigation there. So I got to go out in a boat, and they taught me a few things about navigation. I would really love, at some point, to get way out into Polynesia, maybe, even and be on an authentic ship like they used thousands of years ago and just sort of set sail and, you know, head out for an island you can’t see over the horizon and just navigate with all of the amazing tricks they knew about, you know, the stars but also looking at wave patterns, wind patterns, migration patterns of birds. So at some point I’d love to take a long ocean trip on one of those authentic ships.

Feltman: Very cool. Well, thank you so much for coming on to talk about the book. I’m sure our listeners will love it, so this has been great.

Kean: Well, thanks for having me.

Feltman: That’s all for today’s episode. Don’t forget to check out Dinner with King Tut for more on the wild world of experimental archaeology. We’ll be back on Monday with our usual news roundup.

For Scientific American, this is Rachel Feltman. Have a great weekend!

Rachel Feltman is former executive editor of Popular Science and forever host of the podcast The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week. She previously founded the blog Speaking of Science for the Washington Post.

Fonda Mwangi is a multimedia editor at Scientific American and producer of Science Quickly. She previously worked at Axios, The Recount and WTOP News. She holds a master’s degree in journalism and public affairs from American University in Washington, D.C.

Alex Sugiura is a Peabody and Pulitzer Prize–winning composer, editor and podcast producer based in Brooklyn, N.Y. He has worked on projects for Bloomberg, Axios, Crooked Media and Spotify, among others.

Source: www.scientificamerican.com