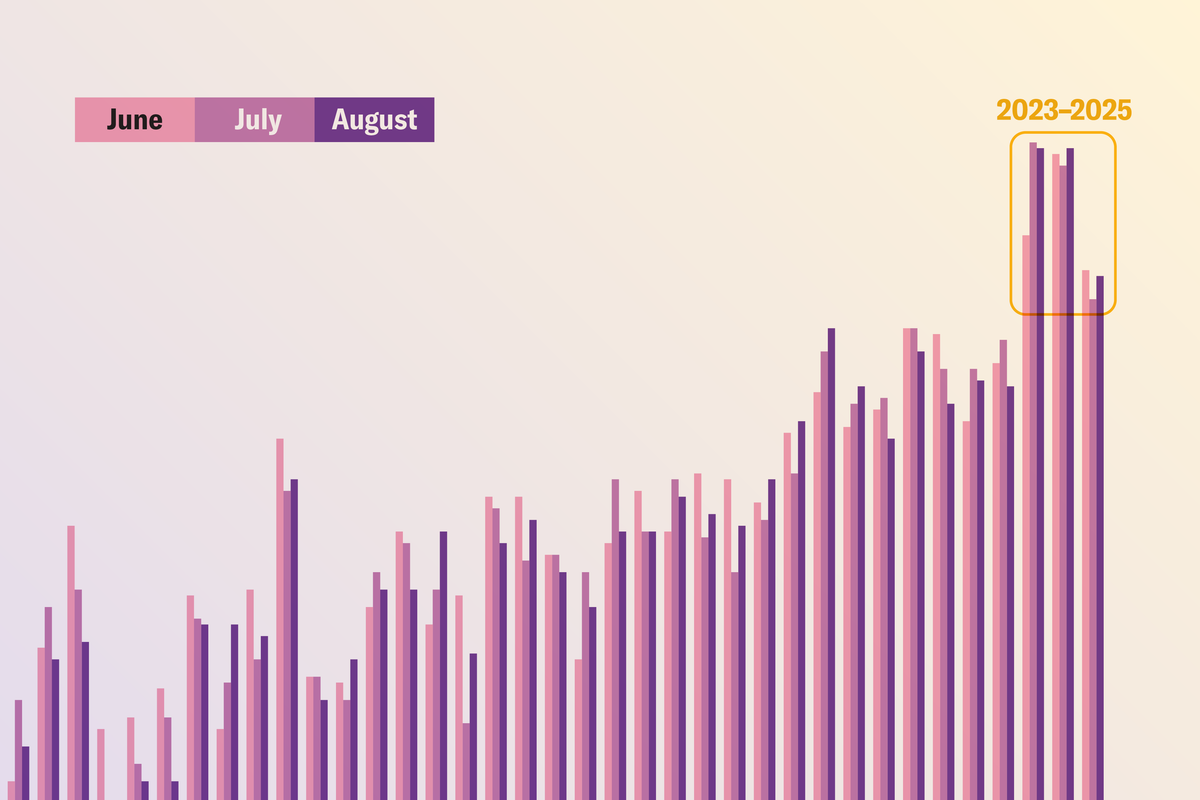

The Past Three Summers Were the Three Hottest on Record

Climate-fueled heat has caused thousands of excess deaths over the past three summers, which were the three hottest on record

The Northern Hemisphere’s summers of 2023, 2024 and 2025 were the three hottest on record, climate agencies in the European Union and the U.S. have announced. This record summer heat was driven primarily by human-caused climate change, which not only has been raising average global temperatures but also has been fueling more lethal heat waves. A new study released on Wednesday finds that climate change likely tripled the number of heat-related deaths in European cities this summer.

“Many of these [people] would not have died without climate change,” said study co-author Friederike Otto, a climate scientist at Imperial College London, during a press conference about the finding.

The June-to-August period of 2025 was the third hottest on record, with a global average temperature 0.47 degree Celsius (0.85 degree Fahrenheit) above the 1991–2000 average, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). (The same period in 2023 was the second hottest, and the one in 2024 has remained in first place.) The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also ranked the Northern Hemisphere’s latest summer as the third hottest in the agency’s 176-year record and measured it as 1.02 degrees C (1.84 degrees F) hotter than the 20th century average.

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

According to NOAA, the current year to date ranks as the second warmest on record, behind 2024. The early part of 2025 featured a weak La Niña, a climate pattern that includes cooler-than-average waters in the tropical Pacific and tends to cool global temperatures. But La Niña years of the past few decades have been even hotter than years in the 20th century that fell under an El Niño, a pattern that tends to raise global temperatures.

The year 2024 was the first on record to have an average temperature more than 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) above the preindustrial era. Under the Paris climate agreement (from which President Donald Trump has once again moved to withdraw the U.S.), countries agreed to try to limit warming to under 1.5 degrees C and “well below” two degrees C (3.6 degrees F). But though reaching the 1.5 milestone for one year is extremely concerning and a marker of how far the world is from reaching those goals, it does not mean the Paris climate threshold has been breached; the accord considers global average temperatures over many years. On that broader timescale, the world is about 1.2 to 1.3 degrees C (2.2 to 2.3 degrees F) above the preindustrial period because of the greenhouse gases that have poured into the atmosphere since that time.

All of the 10 hottest years on record have occurred in the past decade, according to C3S, NOAA and NASA data.

And that number is likely conservative because it covers only about 30 percent of Europe’s population and does not include other regions. “The specifics will vary wherever you’re looking in the world, but the basic point of these studies will always be the same: that we are warming the world through our fossil fuel emissions and other activities and that this is causing people to die,” said Clair Barnes, a climate researcher at Imperial College London, at the press conference. “That’s what it boils down to.”

And the proportion of heat deaths attributable to climate change is creeping up, Otto says.

In the U.S., where heat is the deadliest weather-related killer, residents have gone from experiencing an average of two heat waves each summer in the 1960s to more than six today. Those heat waves have also extended from an average of three days to four—and the heat wave season lasts much longer, extending from just more than 20 days in the 1960s to more than 70 now.

This trend is set to persist as society continues to burn fossil fuels: a 2021 study in Science found that even under countries’ current greenhouse gas reduction pledges, children born in 2020 will experience seven times as many heat waves over their lifetime as people born in 1960. Those future waves will also last longer and feature ever higher temperatures than today’s.

Without more concerted action on the part of governments and companies to rein in emissions, it’s only a matter of time before these record-hot summers are pushed lower down the list—making even today’s record heat seem comparatively cool in the coming decades.

Andrea Thompson is a senior editor covering the environment, energy and earth sciences. She has been covering these issues for 16 years. Prior to joining Scientific American, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered earth science and the environment. She has moderated panels, including as part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Media Zone, and appeared in radio and television interviews on major networks. She holds a graduate degree in science, health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a B.S. and an M.S. in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology. Follow Thompson on Bluesky @andreatweather.bsky.social

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you , you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, , must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.

Thank you,

David M. Ewalt, Editor in Chief, Scientific American

Source: www.scientificamerican.com