Economics Nobel Honors Work Linking Scientific Research to Prosperity

Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt share the Nobel economics prize for work that underlines the importance of investing in research and development

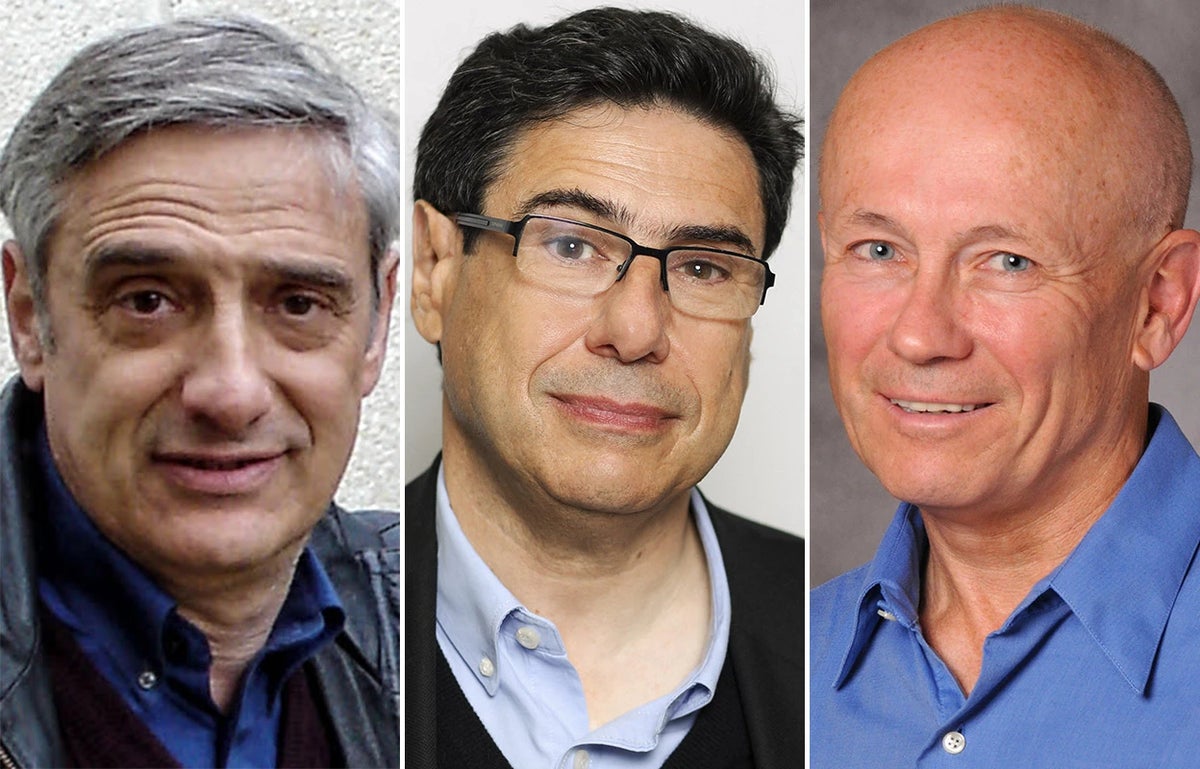

Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, winners of the 2025 Economics Nobel prize.

One half of the prize goes to economic-historian Joel Mokyr of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and the other half is split between the economic theorists Philippe Aghion of the Collège de France and the London School of Economics and Peter Howitt of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

“I can’t find the words to express what I feel,” Aghion said. He says he will use the money for research in his laboratory at the Collège de France.

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Mokyr showed that the key difference between now and then was what he calls “useful knowledge,” or innovations based on scientific understanding. One example is the advances made during the Industrial Revolution, beginning in the eighteenth century, when improvements in steam engines could be made systematic rather than by trial and error.

Aghion and Howitt, for their part, clarified the market mechanisms behind sustained growth in recent times. In 1992 they presented a model showing how competition between companies selling new products allows innovations to enter the marketplace and displaces older products: a process they called creative destruction.

Underlying growth, in other words, is a steady churn of businesses and products. The researchers showed how companies invest in research and development (R&D) to improve their chances of finding a new product, and predicted the optimal level of such investment.

Thus, because companies cannot expect to remain at the forefront of innovation indefinitely, the incentive for investing in R&D coming from market forces alone declines as a company’s market share grows. To guarantee the societal benefits of constant innovation, the model suggests that it is in society’s interests for the state to subsidize R&D, so long as the return is not merely incremental improvements.

The work of all three laureates also acknowledges the complex social consequences of growth. In the early days of the Industrial Revolution there were concerns about how mechanisation would cause unemployment of manual workers – a worry echoed today with the increasing use of AI in place of human labour. But Mokyr showed that in fact early mechanization led to the creation of new jobs.

Their model “recognizes the messiness and complexity of how innovation happens in real economies,” says Coyle. “The idea that a country’s productivity level increases by companies going bust and new ones coming in is a difficult sell, but the evidence that that’s part of the mechanism is pretty strong.”

This year’s award comes at a time when funding for scientific research is under threat in the United States and around the world. “It’s a very timely message when we’re seeing the United States undermining so much of its science base,” says Coyle. Aghion said, “I don’t welcome the protectionist wave in the US” and added that “openness is a driver of growth. I see dark clouds accumulating.” to translate high-tech innovations into market value.

Economic historian Kerstin Enflo, a member of the Nobel prize awarding committee, denied that the award was intended as a comment on the direction of US policies. “It is only about celebrating the work [the laureates] have done,” she said at the press conference.

More recently, researchers are questioning the ‘growth-at-all-costs’ narrative not least because of the ways to pursue growth has led to environmental degradation, including global warming.

“How can we make sure we innovate greener?” Aghion asked. “Firms don’t spontaneously do this. So how can we redirect growth towards green?” Mokyr’s work showed that growth can sometimes be self-correcting in the sense of producing innovations needed to solve such problems. But that is not a given and requires well-crafted policies to nurture innovation without promoting inequality and unsustainability. “We need to harness the productivity potential and minimize the negative effects,” said Aghion.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on October 13, 2025.

Philip Ball is a science writer and author based in London. His latest book is How Life Works (University of Chicago Press, 2023).

First published in 1869, Nature is the world’s leading multidisciplinary science journal. Nature publishes the finest peer-reviewed research that drives ground-breaking discovery, and is read by thought-leaders and decision-makers around the world.

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you , you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, , must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.

Thank you,

David M. Ewalt, Editor in Chief, Scientific American

Source: www.scientificamerican.com