Three NASA Climate Satellites Are Dying. There’s No Plan to Replace Them

Scientists are increasingly concerned about the future of Earth science under President Donald Trump as three key NASA satellites near the end of their missions with no plan for replacement

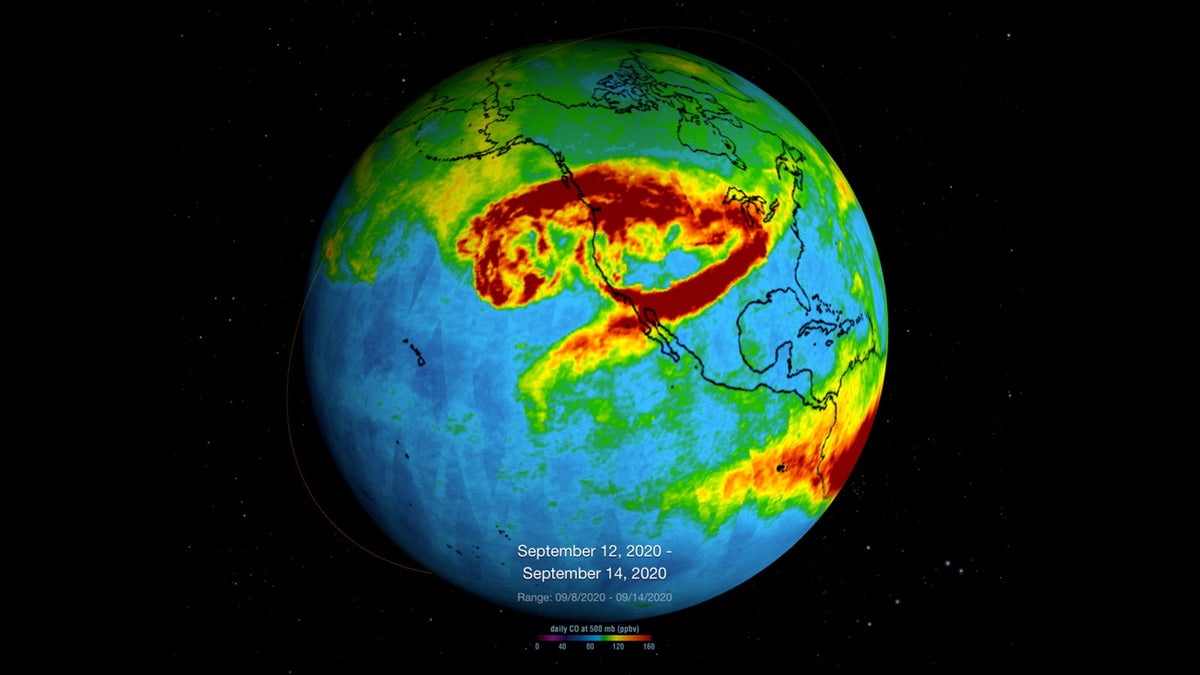

A scientific instrument aboard NASA’s Aqua satellite helps show the spread of carbon monoxide plumes from California wildfires in September 2020.

CLIMATEWIRE | The looming demise of three NASA satellites has scientists bracing for the loss of climate and atmospheric data — especially since there are no plans to replace some of the specialized instruments aboard the Earth-observing probes.

The dying missions — known as the Terra, Aqua and Aura satellites — have been a source of scientific concern for years. Launched one after the other between 1999 and 2004, NASA researchers have always known they had built-in expiration dates. Most instruments don’t work properly forever, and the satellites themselves are running out of fuel, meaning they’re gradually drifting out of their intended orbits.

All three could go dark within the next year. And some of the instruments they carry have no immediate replacements, meaning certain long-term datasets are poised to discontinue. These include climate and environmental measurements, from changes in the Earth’s ozone layer to the solar radiation that warms the planet.

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

That’s a big concern for climate scientists, who use these observations to track the ways the Earth is responding to greenhouse gas emissions. These measurements have grown increasingly important over the last two decades, as the planet’s temperatures have climbed skyward.

“People have come to rely on them, and now they’re going away,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “We’ve been telling people to use our data and to rely on our data, and then we’re not being reliable.”

Some instruments aboard the three probes have no replacements lined up at all, while others have only short-term follow-up missions planned.

Experts say NASA’s long-standing focus on innovation, coupled with funding woes, is part of the reason. NASA’s budgets have remained relatively flat for years, meaning the agency is often forced to choose between older priorities and newer projects — and “given a choice they would rather do something new,” Schmidt said.

The MODIS instrument, on board both the Terra and Aqua satellites, is one cause for concern. Short for Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, it provides a wide range of Earth observations including measurements of forests, clouds, glaciers and oceans.

Similar instruments exist on board certain NOAA satellites, although they don’t provide measurements in the exact same ways. And even if NOAA can collect the same observations, it won’t necessarily analyze the data in a similar manner.

Scientists rely on NASA to interpret the raw data it collects and package it into scientific products that can be used for specific kinds of studies. It’s unclear whether NOAA will provide the same kinds of products after the NASA missions end.

NASA’s CERES instruments — short for Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy Systems — are another worry. These instruments help scientists measure the amount of solar radiation the Earth absorbs, an observation that helps them accurately track global warming.

CERES instruments currently exist on board only four satellites in the world — the Terra and Aqua satellites, plus two other missions operated by NOAA, which are also reaching the ends of their expected lifespans. There’s only one future mission in the works designed to carry CERES instruments, a NOAA satellite scheduled to launch in 2027.

But that mission’s estimated lifespan is only around seven years. And if all the existing CERES satellites fail before it launches, there will be major disruption to the long-term dataset.

Meanwhile, amid widespread cuts across federal agencies over the last two months, some researchers are beginning to worry about the lone follow-on mission scheduled for 2027.

“If this administration decides, ‘We don’t believe in all this hogwash called global warming’ and cut us, then it doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world,” said one NASA researcher involved in the Terra and Aqua missions who asked not to be named out of fear of retaliation from the Trump administration.

Gaps in certain long-term continuous datasets can be almost impossible to accurately fill once the disruption has occurred, the scientist added.

“It’s frustrating to see we have these fundamental measurements of the climate system, they’re not that expensive, but they’re not being done or they’re not being planned,” the scientist said. “It’s kinda scary. It’s unfortunate. This can’t be undone.”

Some lawmakers have pushed for a detailed transition plan for the Terra, Aqua and Aura missions.

One Senate spending proposal for fiscal year 2025 originally included a request for NASA to provide “a transition plan to ensure the continuity of data between the Terra, Aqua, and Aura missions and successor missions or follow-on data sources for instruments” within 120 days.

But the language was not included in the government funding measure ultimately signed by President Donald Trump in March.

“The Terra, Aqua, and Aura missions are still providing important data years after the end of the original mission,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), a ranking member of the Appropriations Commerce, Justice and Science Subcommittee in a statement provided to POLITICO’s E&E News. “That’s why I believe these missions are important to maintain — and wherever possible to extend. I will continue pushing to support these missions and the import insights they provide.”

Concerns over the demise of Terra, Aqua and Aura have predated the Trump administration by years. But scientists are growing increasingly concerned over the future of earth science at NASA against a backdrop of aggressive budget cuts and mass layoffs at the federal science agencies.

NASA science programs are no exception. The Trump administration already has eliminated its chief scientist role, a position formerly held by climate scientist Kate Calvin, who also served as NASA’s senior climate adviser.

In a post on X earlier this month, the Department of Government Efficiency claimed it had terminated $420 million in NASA contracts — although it didn’t specify the eliminated contracts or offer proof of its accounting.

“We’re seeing, in my opinion, a full-scale assault against science across many different agencies,” said Rep. George Whitesides, a California Democrat and former chief of staff at NASA.

Trump’s pick for NASA administrator — billionaire commercial astronaut Jared Isaacman — has yet to be confirmed by the Senate, leaving the agency’s science priorities in limbo.

The Trump administration already has moved to withdraw support for climate research and climate-related grants across federal agencies, and researchers are worried the White House will seek to defund NASA’s Earth-observing science programs. While NASA’s funding from Congress has remained relatively flat in recent years, earth science advocates say these missions deserve more funding.

“Are we spending enough money on earth science to get the data we need to keep our communities safe? I think the answer is probably not,” Whitesides said.

“It has historically been the case that administrations that deprioritize earth science will discontinue missions,” he added. “And my sense is that’s what we’re seeing today. So that’s my top-level concern — is funding.”

Reprinted from E&E News

Chelsea Harvey covers climate science for Climatewire. She tracks the big questions being asked by researchers and explains what’s known, and what needs to be, about global temperatures. Chelsea began writing about climate science in 2014. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Popular Science, Men’s Journal and others.

E&E News provides essential energy and environment news for professionals.

Source: www.scientificamerican.com