See the Dramatic Consequences of Vaccination Rates Teetering on a ‘Knife’s Edge’

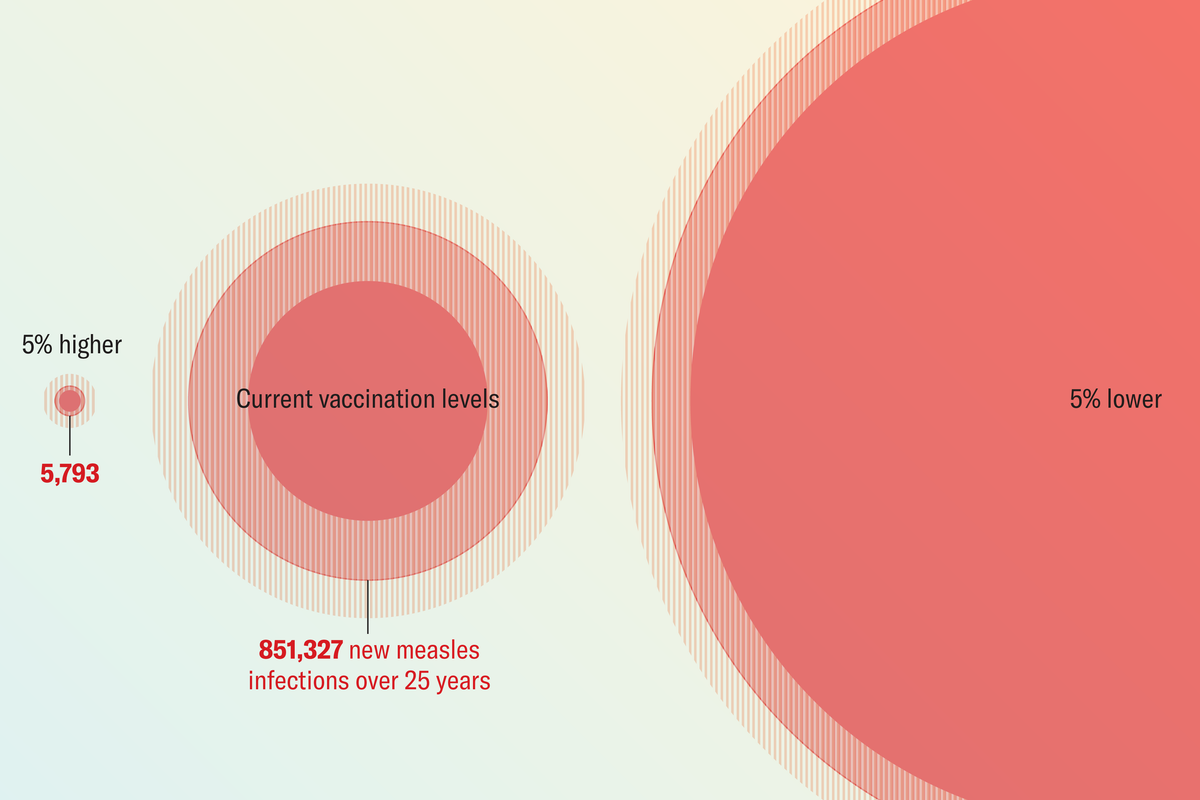

As U.S. childhood vaccination rates sway on a “knife’s edge,” new 25-year projections reveal how slight changes in national immunization could improve—or drastically reverse—the prevalence of measles, polio, rubella and diphtheria

Measles, rubella, polio and diphtheria—once ubiquitous, devastating and deeply feared—have been virtually eliminated from the U.S. for decades. Entire generations have barely encountered these diseases as high vaccination rates and intensive surveillance efforts have largely shielded the country from major outbreaks.

But amid a major multistate measles outbreak that has grown to hundreds of cases, a recent study published in JAMA projects that even a slight dip in current U.S. childhood vaccination rates could reverse such historic gains, which could cause some of these maladies to come roaring back within 25 years—while just a slight increase in rates could effectively squelch all four.

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization formally declare a disease eliminated when there is zero continuous transmission in a specific region for 12 months or more. The U.S. achieved this milestone for measles, a viral illness that can lead to splotchy rashes, pneumonia, organ failure and other dangerous complications, in 2000. Poliovirus, which can cause lifelong paralysis and death, was effectively eliminated from North and South America by 1994. The U.S. rid itself of viral rubella, known for causing miscarriages and severe birth defects, in 2004. And diphtheria, a highly fatal bacterial disease, was virtually eliminated after a vaccine was introduced in the 1940s. These are “key infectious diseases that we’ve eliminated from the U.S. through widespread vaccination,” says study co-author Nathan Lo, a physician-scientist at Stanford University.

Polio and rubella would require sharper vaccination rate downturns (around 30 to 40 percent) before reaching comparable risks of reemergence.

While projected diphtheria cases were notably lower, Lo notes that the illness has a relatively high fatality rate and can cause rapid deterioration: “Patients with diphtheria get symptomatic and within a day or two can die.”

Routine childhood immunization numbers have been slowly but steadily falling in recent years for several reasons, including missed appointments during the COVID pandemic and growing—often highly politicized—public resistance to vaccinations. “The idea of reestablishment of measles is not outrageous and certainly in the moment where we’re looking at erosion of trust through our federal authorities about vaccination,” says Matthew Ferrari, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics at Pennsylvania State University, who was not involved in the study.

Reduced U.S. vaccination rates can also cause “knock-on effects” that threaten disease eradication efforts around the world, Ferrari says. Additionally, recent funding cuts to international vaccine development programs such as USAID and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, will “likely lead to increases in measles, rubella, diphtheria and polio elsewhere in the world,” he says. Outbreaks of these diseases in the U.S. largely start when unvaccinated American travelers pick one up while visiting a place where it’s more common. “If you now add the consequences of defunding vaccination around the world, then that’s going to increase the likelihood of these cases coming to the United States,” Ferrari says, adding that the study authors may have made “conservative assumptions” about these international factors.

But Ferrari says the study’s scenarios assumed immediate—and in some cases unrealistically high—vaccination rate drop-offs without accounting for other possible public health efforts to control disease. “Even if we anticipated an erosion of vaccination in the United States, it probably wouldn’t happen instantly,” Ferrari says. “Detection and reactive vaccination weren’t really discussed in the paper, nor was the population-level response—the behavior of parents and the medical establishment. That’s something we can’t possibly know…. From that perspective, I think the scenarios were enormously pessimistic.”

Lo and Kiang argue that politically driven shifts in vaccine policy, such as reduced childhood vaccination requirements or a tougher authorization process for new vaccines, could make a 50 percent slump in vaccination rates less far-fetched. “I think that there was a lot of pushback from very smart people that 50 percent was way too pessimistic, and I think that—historically—they would have been right,” Kiang says. “I think in the current political climate and what we’ve seen, it’s not clear to me that that is [still] true.”

Kiang and Lo say that while their study shows the dangers of vast vaccine declines, it also highlights how small improvements can make a massive difference.

“There’s also a more empowering side, which is that the small fractions of population that push us one way can also push us the other way,” Lo says. “Someone might ask, ‘What is my role in this?’ But small percentages [of increased vaccination], we find, can really push us back into the safe territory where this alternate reality of measles reestablishing itself would not come to pass.”

Lauren J. Young is an associate editor for health and medicine at Scientific American. She has edited and written stories that tackle a wide range of subjects, including the COVID pandemic, emerging diseases, evolutionary biology and health inequities. Young has nearly a decade of newsroom and science journalism experience. Before joining Scientific American in 2023, she was an associate editor at Popular Science and a digital producer at public radio’s Science Friday. She has appeared as a guest on radio shows, podcasts and stage events. Young has also spoken on panels for the Asian American Journalists Association, American Library Association, NOVA Science Studio and the New York Botanical Garden. Her work has appeared in Scholastic MATH, School Library Journal, IEEE Spectrum, Atlas Obscura and Smithsonian Magazine. Young studied biology at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, before pursuing a master’s at New York University’s Science, Health & Environmental Reporting Program.

Source: www.scientificamerican.com