Your Garbage Has a ‘Wild Afterlife’ on the International Black Market

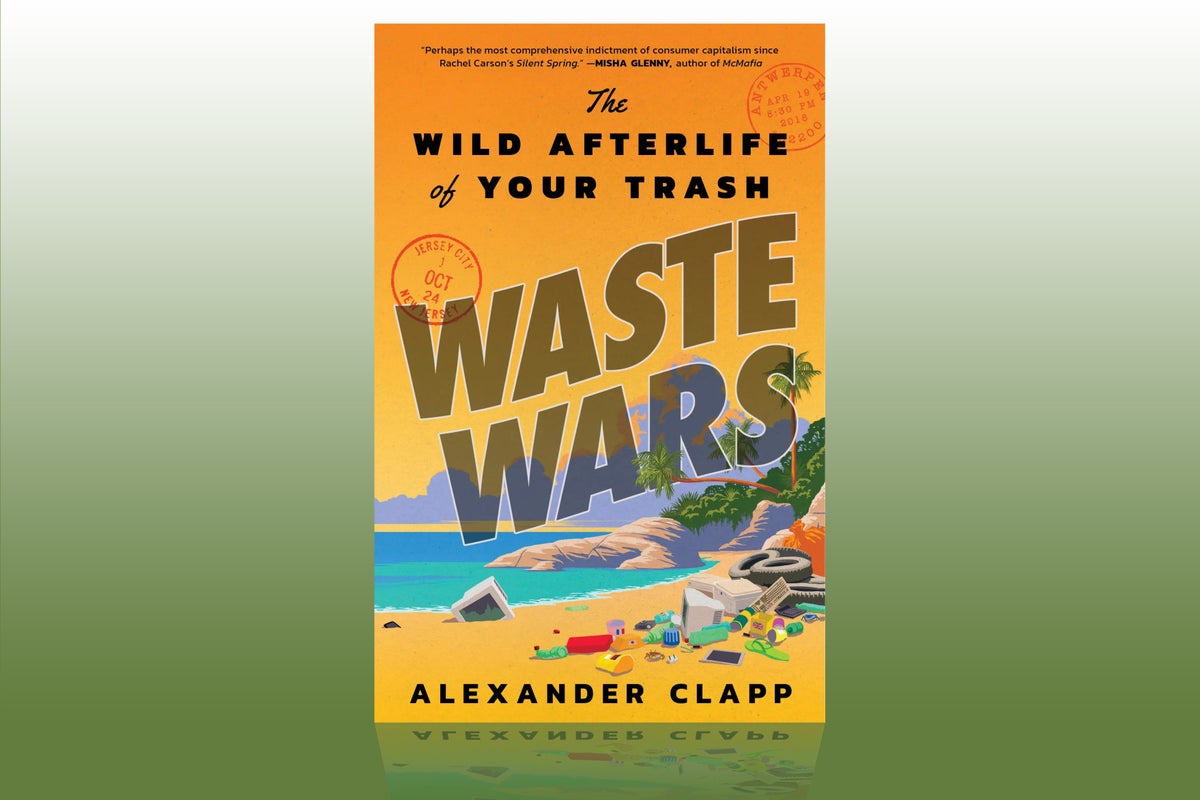

Alexander Clapp, author of new nonfiction book ‘Waste Wars,’ tracks the world-wide blackmarket trade of our garbage

Sorting your trash and recycling is common practice: break down the cardboard boxes, separate the compostable material and plastics and put them into the correct containers, put the trash on the curb, and you’re done. But what happens next is where the story gets interesting. A billion-dollar industry exists around moving countless tons of waste from wealthy countries to poorer ones. For two years journalist Alexander Clapp lived out of a backpack and visited the smelliest parts of the most beautiful places on Earth—looking for hidden dump sites in the Venezuelan jungle and scaling mountains of trash in Ghana—for his new book Waste Wars: The Wild Afterlife of Your Trash. He tracks the massive scope of waste management, from top-level international relations to underground whisper networks, and reveals the dirty underbelly of what happens to our trash.

Scientific American spoke with Clapp about the people who break apart and sort our trash all over the world, the growth of the global waste economy and the future of waste management.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Can you tell me where our exported garbage and not-quite-recyclable goods end up?

It would depend what type of trash we’re talking about, when we’re talking about it or from which country it’s being discarded. But a lot of global trash over the last 30 to 40 years has been going to poor countries under the guise that it’s being recycled. That trash will get broken down, or someone will attempt to make some use out of it—to extract some profit from it—and that’s an extremely dangerous and often lethal process where all sorts of contaminants and forever chemicals enter local ecosystems. They go into the air, they go into the water, and they do huge amounts of damage—damage to, disproportionately, the most vulnerable populations in the world.

That is one of the reasons why I got interested in this topic. We send our waste to the very countries that cannot handle their own domestic waste outputs. I think the dichotomy that’s worth keeping in mind with the waste trade is that it’s not necessarily rich countries versus poor countries; within poor countries, you have importers who are actually buying the waste for pennies, and they are very much part of the problem. The most important thing to understand about the waste trade is that in the 1980s many poor countries felt that they had no option other than to import waste from the so-called global north. They were heavily indebted; they were desperate for factories, ports, industry of any kind. And so I think there’s a really insipid, disturbing history of how and why the waste trade began.

What are you most interested in regarding the future of this waste economy and of waste management on a global scale?

I think what’s really interesting about the global waste trade is that in many ways it’s like the global drug trade. You see organized crime groups that are getting more and more involved in the waste trade because, frankly, the supply of this stuff is endless. The punishment if you get caught moving waste is negligible. I think the future of waste export and waste movement is organized crime. I think they’re going to see this as a monumentally lucrative opportunity.

What was the most shocking story you uncovered while researching for this book?

The most shocking story probably was with the cruise ship-dismantling industry in Türkiye. On the Aegean coast of Türkiye, there’s a [town] called Aliağa where American cruise ship companies disproportionately send a lot of their ships to be dismantled. And you would think that the process of deconstructing a cruise ship would be mechanically refined, but it’s actually kind of this maniacal process done almost entirely by hand where you have armies of helmeted men filing into these cruise ships and breaking this stuff up. One thing that I found was that most of the men who get recruited into doing this work have little idea of what they’re doing. They’ve never seen the ocean before. They were recruited from the middle of Türkiye and given a week’s worth of training. It’s absolutely excruciating.

What was the most surprisingly common occurrence across all of your research?

In terms of the most common story that I would hear, it’s the extent to which in poor countries trash, and especially plastic, is just regarded as another commodity. Generally [the people I encountered didn’t] think about this stuff as a potentially toxic substance. That was shocking to me. In places such as Java and [other parts of] Indonesia, hundreds of tons of Western plastic are imported every week and used as fuel in tofu factories, and then that tofu gets exported around the world’s most populous island [Java]. I was just struck by how kind of pedestrian it seems to just burn plastic in places to get rid of it or to find some use for it.

Brianne Kane is the editorial workflow and rights manager at Scientific American.

Source: www.scientificamerican.com