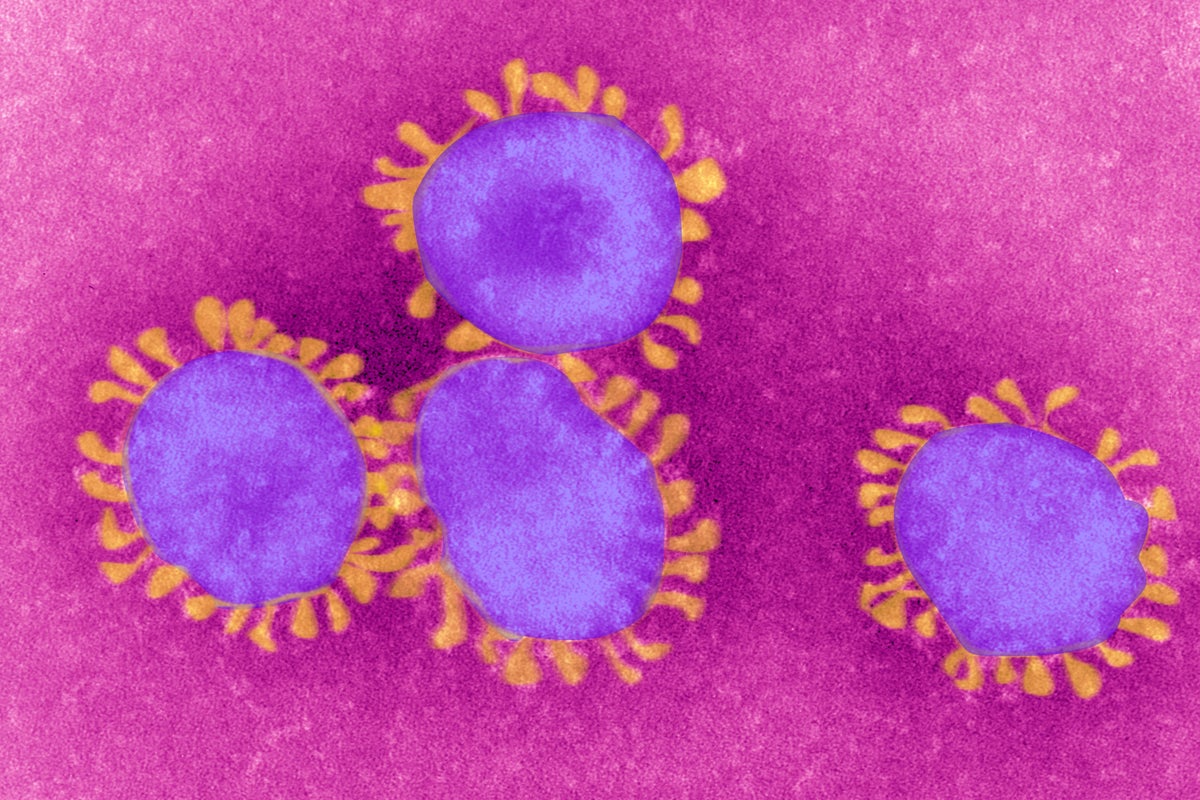

COVID During Pregnancy May Raise Autism Risk, Study Suggests

A new study adds to the evidence that viral infections during pregnancy might contribute to a child’s likelihood of having autism

Join Our Community of Science Lovers!

People who catch COVID while pregnant might have a higher likelihood of having a child who is later diagnosed with autism or another neurodevelopmental condition, a new study has found. The results add to previous research showing that, among other factors, infections in general during pregnancy are linked to autism risk for the child. They do not, however, suggest that everyone who has COVID while pregnant will have a child with autism.

“Even though there’s an increased risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders, the absolute risk still remains relatively low, especially for autism,” says study senior author Andrea Edlow, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, referring to having COVID during pregnancy.

For the study, published Thursday in , Edlow and colleagues looked at electronic health records of more 18,000 births that occurred between March 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, during the first year of the COVID pandemic. They compared the likelihood of a neurodevelopmental diagnosis in children born to individuals who had a positive COVID PCR test during pregnancy with those who didn’t.

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Of the 861 children born to people who had COVID during pregnancy, 16.3 percent went on to receive a neurodevelopmental diagnosis by age 3 compared with 9.7 percent of the 17,263 children born to people who hadn’t had COVID. The diagnoses included not just autism but also speech and language disorders, motor function disorders, and other conditions. When the researchers controlled for various confounding factors, COVID infection during pregnancy was linked to increased odds of these conditions of nearly 30 percent.

The findings add to a body of evidence—mainly in animals but also in humans—suggesting that various infections during pregnancy, such as influenza or rubella, are linked to a higher risk of having a child with autism or a similar condition. Because SARS-CoV-2 rarely crosses the placenta, scientists hypothesize it’s not the virus itself upping the risk. Rather they suspect immune activation in the pregnant person could be responsible.

The strongest associations in the new study were for COVID infection in the third trimester and for male offspring. (The increase in odds was not significant for female offspring.) The third trimester is a critical time for fetal brain development, and boys are diagnosed with autism at higher rates than girls in general.

The study also didn’t specifically control for vaccination status, although very few individuals had been vaccinated during the study period because the COVID vaccine wasn’t widely available at the time. Previous research has shown that vaccination protects pregnant people—who are more likely to get very sick and die from COVID—and their fetuses from the disease.

The study findings come on the heels of controversial statements made by President Trump and Health and Human Services secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., linking Tylenol (acetaminophen) to autism—which the best available evidence does not support. Numerous studies have also shown that vaccines do not cause autism.

It’s important to note that autism is a complex spectrum of conditions—not all of which cause disabilities—with many contributing factors. Genetics is thought to have the biggest influence, but environmental factors such as infection may also play a role.

Tanya Lewis is a senior editor covering health and medicine at Scientific American. She writes and edits stories for the website and print magazine on topics ranging from COVID to organ transplants. She also appears on Scientific American‘s podcast Science, Quickly and writes Scientific American‘s weekly Health & Biology newsletter. She has held a number of positions over her eight years at Scientific American, including health editor, assistant news editor and associate editor at Scientific American Mind. Previously, she has written for outlets that include Insider, Wired, Science News, and others. She has a degree in biomedical engineering from Brown University and one in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Follow her on Bluesky @tanyalewis.bsky.social

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you , you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, , must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.

Thank you,

David M. Ewalt, Editor in Chief, Scientific American

Source: www.scientificamerican.com