It’s Nearly Time to Say Goodbye to the International Space Station. What Happens Next?

Humans have been in space onboard the ISS continuously for 25 years. As the station nears its end, new commercial habitats are lining up to take its place

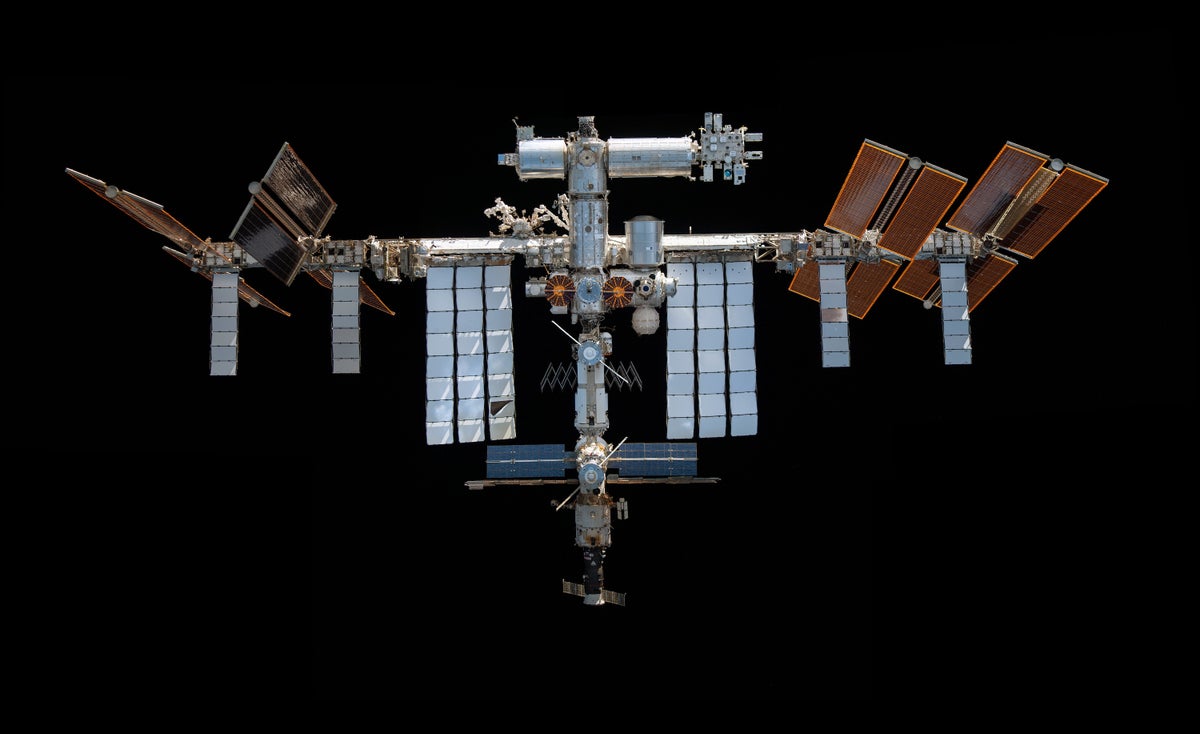

The International Space Station, as seen from the SpaceX Crew Dragon Endeavour spacecraft on November 8, 2021.

Human spaceflight is on the cusp of an intriguing new dawn. For 25 years, astronauts have lived and worked onboard the International Space Station (ISS), starting with the arrival of its first occupants on November 2, 2000. Built through a partnership between the U.S. and Russia in the aftermath of the cold war, the ISS has now witnessed five presidential administrations, the advent and demise of the iPod and even the lofting of another orbital habitat, China’s Tiangong space station. But the ISS’s days are numbered. By 2031, NASA plans to deorbit the space station. Citing aging hardware and rising costs, the agency will bring it back through Earth’s atmosphere for a fiery plunge into the Pacific Ocean.

If all goes as planned, commercial space stations—outposts operated not by government agencies but instead by private companies—will take the ISS’s place to build on its success. The first of these is set to launch next year, with a slew of others scheduled to follow soon after. All of them have the same goal of fostering a vibrant, human-centered economy in Earth orbit—and ultimately beyond.

“We hope to build habitats for the moon [and] Mars and eventually even an artificial-gravity space station,” says Max Haot, CEO of Vast, a Long Beach, Calif.–based company at the forefront of the private-sector spacefaring push. Vast plans to launch its Haven-1 space station as soon as May 2026. On Haven-1’s heels will be several other habitats from Axiom Space, Blue Origin and Starlab Space. All of them are intended to reach orbit by the end of the decade (and are still somewhat reliant on NASA as a paying customer).

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The ISS will leave behind an important legacy, says Bill Nelson, who was formerly a U.S. senator and a space shuttle crew member, as well as NASA’s administrator from 2021 to 2025, and formalized the time line for the nation’s pivot to commercial space stations. “The station has done incredible things,” he says, from establishing how to live safely in space to exploring the promise and peril of microgravity environments. All the while, the ISS has been a shining beacon of global cooperation.

NASA’s shift from “operator” of the ISS to a “tenant” on space stations, Nelson says, should help the agency focus on more innovative and daring explorations deeper in the solar system. “It’s part of the evolution of space,” he adds. “It used to be all government. Now we have commercial partners and international partners.”

Some have argued that the ISS could still have a long life ahead if it were to be boosted to a higher orbit, where it could endure intact for decades or centuries. “I think it’s the most amazing thing that humanity has ever constructed,” says Greg Autry, a space policy expert at the University of Central Florida. “It’s kind of like deorbiting Buckingham Palace. It’s an amazing historical structure, and it should be recognized for that.” NASA, however, determined that rescuing the ISS would be too costly and complex. Instead the space agency opted to pay SpaceX nearly $1 billion to develop a vehicle that will push the station back into Earth’s atmosphere in 2031, leaving China’s Tiangong space station as the only government-run outpost in orbit.

By the time that happens, multiple commercial space stations could be active. Haven-1, the first of them, is a singular, camper-van-sized structure that will be launched on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. Initially lofted uncrewed, the station will offer stays of up to 10 days for both governmental and private-sector visitors, all of whom are planned to reach Haven-1 via a SpaceX Dragon capsule. The cost of a private booking is undisclosed at present.

“Our core business model is 85 percent sovereign space agencies, including NASA, and then maybe 15 percent private individuals,” Haot says. Onboard, four occupants will have private sleeping berths with inflatable beds, a domed window to observe Earth and high-speed Internet provided by SpaceX’s Starlink service. A built-in science lab will allow them to conduct research at the station.

Haven-1 is a precursor to a much bigger construct planned by Vast called Haven-2, which is expected to launch by the time the ISS is abandoned. Haven-2 will comprise multiple Haven-1-style modules arranged in a cross shape to enable a continuous human presence in orbit rather than short stays like Haven-1 will host. It will be joined by the other commercial ventures—Axiom Station, Blue Origin’s Orbital Reef, and Starlab.

New priorities may come with any new private era in Earth orbit. Whereas the ISS was notionally a station focused on science, private habitats will inevitably have a broader purview, from acting as proverbial space hotels to being manufacturing hubs for products imported back to Earth. “You can make much better silicon crystals [for semiconductors] in space,” says Autry, listing one of several perennial arguments for more industrial activity in orbit. “[There are] a lot of different economic drivers that I think will eventually pay off,” and the space tourism business “will be much larger than most people believe.”

Autry points to Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket, which launches paying customers straight up and down on suborbital rides lasting just 10 minutes but has already flown about 80 people (including some repeat customers). “There’s a really strong demand,” he says, arguing that an increase in rides to space—and destinations to reach—shows space tourism can “absolutely” be as accessible as other extreme environments, such as the deep sea. “There’s no reason you can’t get suborbital ticket prices into the thousands of dollars and orbital ticket prices under $1 million,” he says. “I think it will happen in the next 10 to 20 years.”

Research institutions and universities could increase their access to space, too, perhaps by sending their own astronauts. Earlier this year, for example, Purdue University booked tickets for a 2027 flight on Virgin Galactic’s suborbital space plane for a pair of its researchers. It’s not unfathomable to think the same might occur on commercial space stations, especially if the cost of visiting them can be brought down to a reasonable level.

Commercial space stations, Scharf says, might be the next step in this journey—but he’s not quite ready to buy a ticket—or the hype. “Maybe we’ll learn that commercial space stations are the best thing ever,” he says. “Or perhaps we will discover that this isn’t actually the be all and end all. It’s absolutely possible that commercial space stations, for economic or financial reasons, do not yield what is expected or hoped.”

By the end of the decade, humans are also planned to return to the moon in competing efforts, one led by the U.S. and the other led by China. Ian Crawford, a planetary scientist at Birkbeck, University of London, has previously argued that space stations can be a distraction from this endeavor. “To talk about space exploration properly, we have to move away from low-Earth orbit,” he says. “How ‘space hotels’ in Earth orbit really feed into that, I don’t know.”

Whatever direction these new stations take, they will mark the end of a historic experiment—a full quarter-century (and counting) of humans living and working off-world. The feat is all the more remarkable for how unremarkable it now appears: More than 40 percent of all the people on Earth are younger than the ISS, having never known a world without it. For many of them, the station’s quiet technical triumph of unbroken orbital occupation is understandably banal, boring and routine. That is to say, like so many wondrous things we take for granted, it seems the ISS won’t really be understood for its good until it’s gone.

Jonathan O’Callaghan is an award-winning freelance journalist covering astronomy, astrophysics, commercial spaceflight and space exploration. Follow him on X @Astro_Jonny

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you , you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, , must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.

Thank you,

David M. Ewalt, Editor in Chief, Scientific American

Source: www.scientificamerican.com